Belief is a fundamental aspect of the human experience. It shapes our perceptions, drives our actions, and molds our understanding of the world. However, belief is not a binary state—it’s not a simple matter of believing or disbelieving. Belief and disbelief exist on a spectrum, a nuanced continuum where the strength of our convictions should be directly proportional to the amount and quality of evidence available.

Understanding the Spectrum of Belief

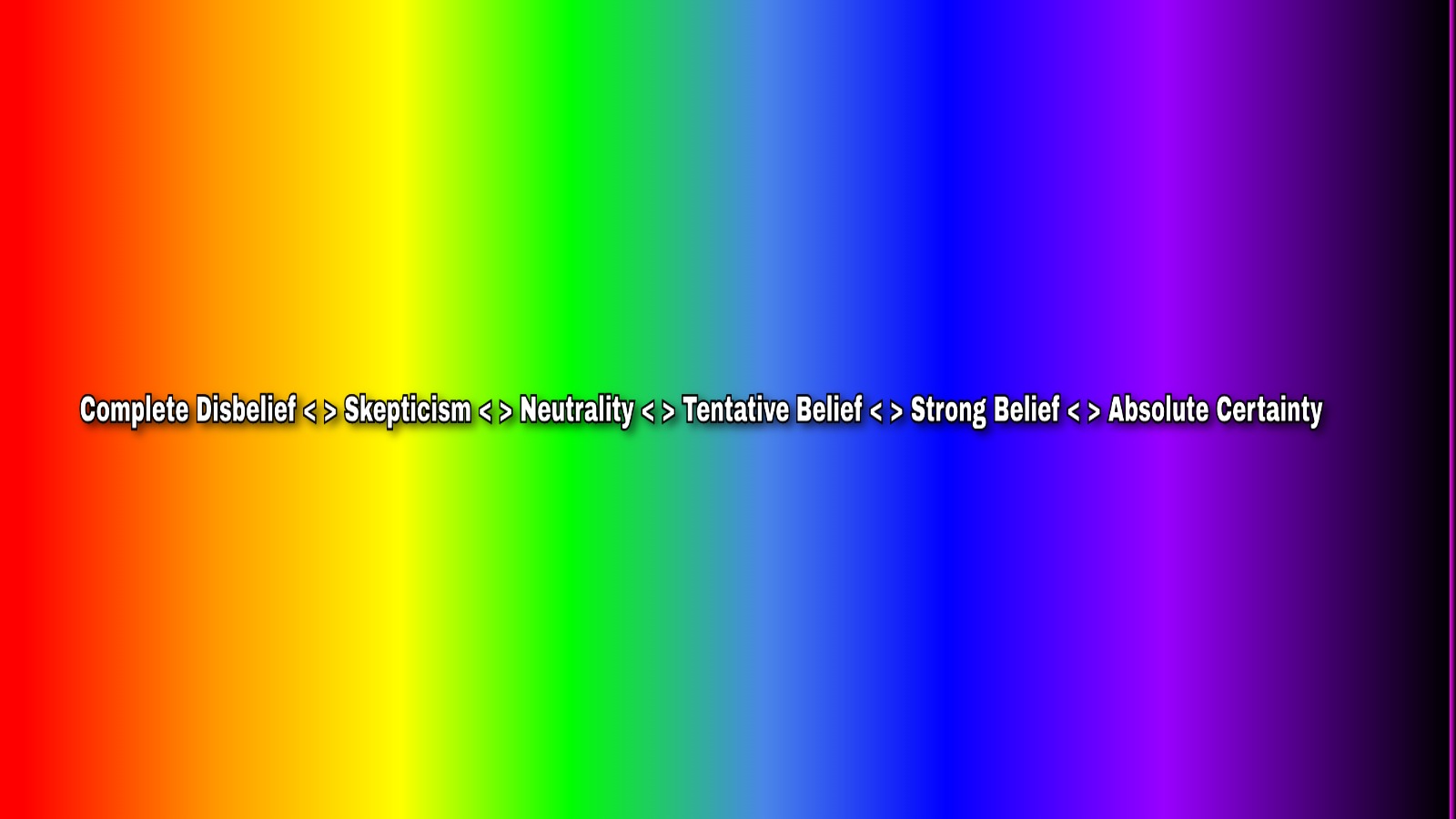

The idea that belief exists on a spectrum challenges the traditional dichotomy of belief versus disbelief. This spectrum ranges from absolute certainty on one end to complete skepticism on the other, with various degrees of confidence in between. Imagine this spectrum as a line:

Most of our beliefs fall somewhere along this line, influenced by personal experiences, societal norms, education, and the evidence at hand.

Evidence is the cornerstone of rational belief. To navigate the spectrum of belief wisely, we should apportion our belief according to the quality and quantity of evidence. This approach is central to critical thinking and scientific inquiry, ensuring that our beliefs are grounded in reality.

High-quality evidence comes from reliable sources, is observable, quantifiable, replicable, and withstands scrutiny. For instance, scientific studies published in peer-reviewed journals offer stronger evidence than anecdotal reports because of the methodologies they use. When high-quality evidence like scientific studies support a claim, we can move further along the spectrum towards strong belief or certainty.

The quantity of evidence also matters. A single study or a single observation may suggest a particular conclusion, but multiple studies or observations over time, providing consistent results, offer a stronger basis for belief. Conversely, a lack of evidence or contradictory findings should temper our beliefs, moving us further along the spectrum towards skepticism or neutrality.

In our daily lives, we constantly make decisions based on varying levels of evidence. When choosing a medical treatment, we rely on clinical trials and expert recommendations like referrals from our doctors. For less critical decisions, like selecting a restaurant, we might depend on reviews and personal recommendations from friends or family members. In both cases, the strength of our belief in the choice we made should match the available evidence.

The scientific method relies on the principle of apportioning belief to evidence. Hypotheses are tested, and conclusions are drawn based on empirical data. Scientists remain open to changing their beliefs as new evidence emerges, illustrating the fluid nature of belief on the spectrum. If a scientific study can be demonstrated to be inaccurate, then legitimate scientists re-adjust their beliefs to incorporate the new information.

Moral and philosophical beliefs also benefit from evidence-based reasoning. Ethical and moral systems and philosophical theories should be evaluated based on logical consistency, empirical support, and practical outcomes. While some beliefs may be deeply personal or culturally influenced, examining them through the lens of evidence can lead to more reasoned and justifiable positions.

Failing to apportion belief to the amount of credible evidence available can lead to extremism on both ends of the spectrum. Blind faith, or absolute certainty without sufficient evidence, can result in dogmatism and resistance to new information. On the other hand, excessive skepticism can lead to cynicism and the rejection of well-supported ideas, hindering progress and understanding. The way to figure out if a person is on either extreme of the spectrum is to ask them a single question: “What evidence would be good enough to change your mind or convince you that your opinion is wrong?”

If the answer to that question is, “No amount of evidence would change my mind,” then that person’s beliefs aren’t based on facts or evidence.

Acknowledging that beliefs exist on a spectrum allows us to embrace uncertainty. It’s okay to say “I don’t know” or “I’m not sure” when evidence is lacking or inconclusive. This humility opens the door to ongoing inquiry and learning, fostering a mindset that values evidence over preconceived notions. On the other hand, claiming we have an answer when the evidence is unclear or uncertain opens us up to the gullibility of falling for all sorts of crackpot theories and conspiracies.

So what does all of this have to do with the supernatural and the paranormal?

Belief is not a binary state but a spectrum that requires careful navigation. When faced with an unexplained phenomenon, we should strive to seek a rational explanation while determining to keep open-minded to the possibilities. By apportioning our belief to the amount and quality of evidence available, we can cultivate a more rational, flexible, and open-minded approach to understanding the world.

For example, if we see an unexplained phenomenon in the sky that we cannot identify, does it automatically mean that the phenomenon is an alien spacecraft, or does it mean that we just saw something unidentified? Even if we’d like to believe that it is indeed alien visitors, do we have enough credible evidence to support such a conclusion, or should we place it somewhere on the spectrum, perhaps towards the “tentative belief” portion?

Note also that if we withhold judgment until more evidence is made available, that doesn’t mean that it isn’t an alien spacecraft either. We’re just choosing to apportion our credulity to the amount of data we have to make decisions with.

Embracing this belief spectrum not only enhances our decision-making but also enriches our capacity for growth and discovery. In a world filled with information and complexity, much of which is designed to misinform or mislead us, this approach offers a guiding principle for discerning truth and fostering meaningful beliefs.